Joshua Finnell*

On 9 May 2013, US President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 13642-Making Open and Machine Readable the New Default for Government – mandating, wherever legally permissible and possible, that US Government information be made open to the public.[1] This edict accelerated the construction of and framework for data repositories, and data citation principles and practices, such as data.gov. As a corollary, researchers across the country’s national laboratories found themselves creating data management plans, applying data set metadata standards, and ensuring the long-term access of data for federally funded scientific research.

Inspired by President Obama’s new era of transparency, a project team at Harvard University’s Library Innovation Lab, in partnership with Ravel Law, recently launched the Free the Law project. During a recent panel at the American Bar Association Techshow, Adam Ziegler, a member of the project team, remarked, “We are in an era of amazing progress in access to government data, but where are we with the law? Almost nowhere, unfortunately.”[2] The goal of the Free the Law project is to digitize all US state, federal, and territorial and pre-statehood legal decisions in Harvard Law School Library’s collection.[3] By 2017, the project team hopes to digitize over forty million pages of United States case law. Though Ravel Law will receive an 8-year exclusive commercial license for redacted files, Harvard University will own all the data and is allowed to provide public access to the redacted files.[4]

It was almost forty years ago, on 18 July 1979, that US President Jimmy Carter issued Executive Order 12146-Management of Federal Legal Resources – tasking Griffin Bell, the US Attorney General, and Harold Brown, the Secretary of Defense, among other federal agency heads, with making legal information both publicly accessible and automated.[5]

1-501. In addition to the disclosure now required by law, all agencies are encouraged to make available for public inspection and copying other opinions of their legal officers that are statements of policy or interpretation that have been adopted by the agency, unless the agency determines that disclosure would result in demonstrable harm.

1-601. The Attorney General, in coordination with the Secretary of Defense and other agency heads, shall provide for a computerized legal research system that will be available to all Federal law offices on a reimbursable basis. The system may include in its data base such Federal regulations, case briefs, and legal opinions, as the Attorney General deems appropriate.

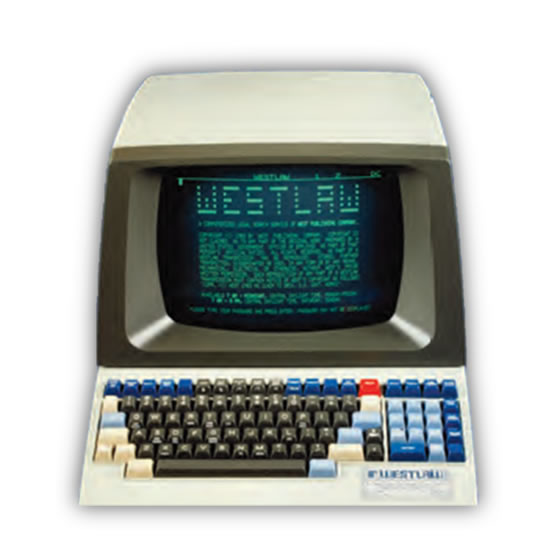

This mandate resulted in the Department of Justice contracting the firm of Coopers & Lybrand (better known today PricewaterhouseCoopers) to assess the utility and cost of three competing computer-assisted legal research systems: WestLaw, Lexis Nexis, and the pre-existing Justice Retrieval and Inquiry System (JURIS).[6] This report marks the genesis of a legal informatics stage drama that would find all three systems operating independently, in unison, and in competition with one another for the next decade and a half, culminating in the permanent shutdown of JURIS by the Clinton administration on January 1, 1994.[7]

While Lexis Nexis and Westlaw continued to flourish in the marketplace, the Federal Judiciary’s Electronic Public Access Program began piloting the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) system. In 2001, the Judicial Conference of the United States released a Web-based version of PACER to the public, allowing the general public to download court documents for a small fee.[8] However, those who have had the pleasure of using PACER know all too well it lacks both functionality and precision. Unless one has a keen understanding of the complexities of US court filings, a simple request may result in hundreds of pages of unrelated case law. Hence, the nominal fee of eight cents per page could aggregate quickly with multiple requests. In 2008, Aaron Schwartz, an American internet ‘hacktivist’, was subject to an FBI investigation after utilizing a free trail of PACER to download 2.7 million records, subsequently forcing the Government Printing Office to suspend the free trial.[9] Those records would eventually be loaded into RECAP, a free browser extension for Firefox and Chrome that allows free access to PACER documents.[10]

From Jimmy Carter to Barack Obama, the hope for a more transparent and open government has been slowly evolving. The data deposits and open-access requirements of the United States’ federally funded research has opened up larger discussions about research redundancy and reproducibility. Let’s hope projects like Harvard’s Free the Law Project, RECAP, and all of the organizations and individuals involved in the Free Access to Law Movement continue to push for more transparency and free access to US case law.

*Scholarly Communications Librarian, Los Alamos National Laboratory

[1] Executive Order 13642—Making Open and Machine Readable the New Default for Government Information of May 9, 2013, available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2014-title3-vol1/pdf/CFR-2014-title3-vol1-eo13642.pdf (accessed 21 March 16).

[2] L Laird, “As Governments Open Access to Data, Law Lags Far Behind” (2016) available at http://www.abajournal.com/news/article/as_governments_open_access_to_data_law_lags_far_behind (accessed 20 March 16).

[3] Harvard University Library Innovation Lab, “Project: Free The Law” (2015) available at http://librarylab.law.harvard.edu/projects/free-the-law (accessed 23 March 16).

[4] A Ziegler, “Free the Law – Overview” (2015) available at http://etseq.law.harvard.edu/2015/10/free-the-law-overview/ (accessed 24 March 16).

[5] Executive Order 12146—Management of Federal Legal Resources of July 18, 1979, 44 FR 42657, 3 CFR, available at http://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12146.html (accessed 22 March 2016).

[6] Coopers & Lybrand/U.S. Department of Justice, “An Analysis of the Justice Retrieval and Inquiry System (JURIS): Final Report” (1979) available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/75871NCJRS.pdf (accessed 20 March 16).

[7] J Bing, “Let There Be Lite: A Brief History of Legal Information Retrieval” in A Paliwala (ed), A History of Legal Informatics (Spain: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, 2014) 46-47.

[8] S Lyons, “Balancing Access and Privacy: Free Pacer” (2009) American Association of Law Libraries Spectrum 30-33, at 30.

[9] J Schwartz, “An Effort to Upgrade a Court Archive System to Free and Easy” (2009) New York Times A16.

[10] RECAP, “RECAP The Law” (2016) available at https://www.recapthelaw.org/ (accessed 21 March 16).

Pingback: Open Data and the Free Access to Law Movement in the United States – Veille juridique