Simone Schroff*

Abstract

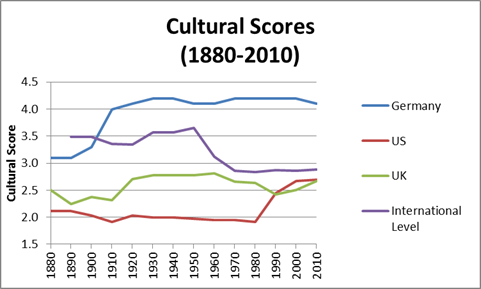

In the literature on copyright evolution, it has been argued that some degree of convergence has occurred over time. This means that the respective policies of different jurisdictions have become increasingly similar, not only in the substantive provisions themselves (the scope of protection) but also in how copyright is perceived (the copyright culture). Copyright culture in particular refers to the well-established, idealised models of author rights generally associated with civil law systems and common law copyright. Nonetheless, recent technological challenges have highlighted the significant differences that remain in how copyright responds to new challenges. This article examines the convergence of copyright policies in the US, UK, Germany and international level between 1880 and 2010. Rather than relying on a qualitative analysis, a quantitative approach is used to examine the evidence for convergence. It compares the laws as they are in force for each of the jurisdictions examined, to the two ideal types relied upon by the legal literature: author rights systems and common law copyright systems. Ideal types reflect the epitomised description of what an author rights and a common law system are, irrespective of whether these exist or have existed in such a form in the real world. These two polar opposites are used as external benchmarks against which the copyright policies are compared and the position of these policies on a spectrum which has author rights at one end and common law copyright at the other, is determined. By placing the case studies on a spectrum, their evolution relative to each other is clear and the existence of convergence and its extent can be analysed. The article concludes by clarifying the extent of convergence. The degree of convergence has been limited between the US, UK and international level, while Germany’s policies actually moved away from them. In addition, the commonly identified causal factors, such as technology and international agreements, only developed a limited impact in practice, explaining why the empirical evidence has failed to show the expected convergence.

Cite as: S Schroff, “The (Non) Convergence of Copyright Policies – A Quantitative Approach to Convergence in Copyright”, (2013) 10:4 SCRIPTed 411 http://script-ed.org/?p=1210

Download PDF

DOI: 10.2966/scrip.100413.411

© Simone Schroff 2013

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

1. Introduction

In the last 20 years, copyright policy has been a core item on the national and international agenda. The rise of online piracy especially has highlighted the importance of consistent cross-country protection and triggered a flurry of legislative and harmonisation efforts at the national and international level (among others: the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), the EU and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). However, inconsistencies between countries remain and their impact on other policy areas is profound, for example the Google Book Library Project.

1.1 Literature Review: Convergence in Copyright Policy

Responses to new challenges like digitisation are largely determined by a country’s general understanding of copyright: its legal culture. The literature identifies a number of common factors that have triggered increasing similarity between national policies. Firstly, copyright is an inherently international issue.[1] Copyrighted works have always been transported and traded across borders. As a result, there have been strong pressures in ‘copyright exporting’ countries to ensure adequate protection in other systems.[2] There have been a large number of agreements over the years aiming to ensure a minimum standard of protection in all member states, for example the Berne Convention (1886 and its revisions) and the TRIPs agreement (1994).[3] These agreements, however (especially early ones), were not intended to cause convergence. Rather, the aim was to provide for national treatment and minimum standards amongst countries.[4] Nonetheless, they do contribute to convergence in practice because they bridge the systematic differences between different copyright conceptions.[5] The strongest influence in this respect is attributed to the Berne Convention. Convergence here is the result of spreading certain copyright features, for example requiring that member states ensure a minimum term of protection (life plus fifty years) and the protection of moral rights.[6] Another multilateral framework for coordination is provided by the EU. The EU has member states from both legal families and this is reflected in its copyright provisions which includes cultural features from both groups.[7] The effectiveness of EU attempts at convergence is considered particularly strong because of its enforcement capabilities.[8]

The domestic pressure for international protection can also lead to unilateral action. The US especially has pushed for further protection at both the international level and third countries’ national legislation.[9] In doing so, it actively aimed to have its own approach implemented at the international level.[10] One key example here is the explicit exclusion of moral rights from the TRIPs agreement.[11] Finally, new technologies challenge copyright by creating loopholes and therefore triggering a regulatory response.[12] In an environment characterised by significant international communication, these responses are expected to be similar.[13] As countries discuss the issues, and especially the possible solutions, at the international level, these ideas spread from one country to the next and enter the domestic debates. This naturally increases the likelihood of jurisdictions adopting similar approaches to challenges.

As a result of these forces, commentators refer to a convergence in copyright policy. This is either assumed or argued in reference to the literature on copyright law in (comparative) legal studies.[14] The methodologies used vary and range from traditional doctrinal legal analysis to statistical analyses.[15] However, there is disagreement on the extent of convergence. Those focusing on the actual provisions, rather than functional equivalence, have identified growing similarities as systems move towards each other.[16] In this respect, cultural variations are seen as historical artefacts. However, there is no claim that convergence has been complete.[17] They especially point out that full convergence may be impossible as the remaining variations have high political salience: they affect core cultural differences.[18] On the other hand, the functional school of thought argues that these remaining discrepancies, on the surface, do not prevent full functional convergence. The systems lead to the same outcome despite the different approaches used.[19] In this sense, the variations are seen as very minor. They do not affect the substance of protection and are too small to be of systematic relevance.[20] The systems have moved closer to each other: they agree on the appropriate protection although the means to achieve this vary.

In conclusion, the literature disputes the extent of convergence but the evidence is limited. Depending on the school of thought, the impact of the remaining differences varies between irrelevance and representing core cultural assumptions. In either case, copyright policies have become more similar over time as the systems move towards each other. However, recent developments contradict the literature, as the impact of the differences is extensive and highly significant. For example, the varying responses to major undertakings, such as the Google Book project, demonstrate that the solutions to technological challenges still vary both in form and substance.[21] Since 2004, Google has digitised complete books to make them at least partially available online – irrespective of their copyright status and without the explicit consent of the copyright holders. Although this practice of digitisation has been permissible in the US, it has been considered infringing in the EU.[22] However, the resulting European digitisation alternative, Europeana, has only made slow progress with strong variations in development between member states due to the differences in digitisation exemptions for archival purposes and the procedures for making these available online.[23] Therefore, a longitudinal study, utilising a more systematic and objective approach to examine the evolution of copyright across countries is required to shed light on this contradiction.

1.2 Scope of Research

This study investigates convergence from the point of view of four case studies. These case studies comprise of three countries (the UK, Germany and the US) and the international law dimension. These case studies were selected for their cultural background as well as their economic strength. The UK and Germany are the economic powerhouses in the EU. Germany is a civil law country while the UK’s copyright system is based on common law: they belong to different legal cultures. It should be noted that France is often used instead of Germany as the ideal civil law country in the field of copyright policy. France’s role in these comparisons is that of a benchmark because it is seen as the most representative case study for the civil law approach to copyright. However, research has shown that France has never fully met this standard: it has never adopted a pure civil law approach.[24] As a result, this article relies on a theory-based ideal type to provide the standard of comparison.[25] In addition, the discourse on copyright is dominated by economic concerns, for example copyright as a major contribution to a country’s competitiveness and economic growth.[26] Therefore, the economically stronger Germany is chosen instead of France. The US is included for its economic strength and to isolate the influence of EU membership. Finally, given the importance of the international dimension, the different multilateral agreements are treated as a distinct system by aggregating the individual provisions.[27] In essence, it represents a kind of ‘super-agreement’ reflecting the strongest level of protection possible at the international level that a state would benefit from if it joined all of these agreements.[28]

The time frame covers 1880-2010 and the state of the provisions are determined for every 10 years. The long time frame is necessary to isolate the influence of international coordination, especially the 1886 Berne Convention. The focal point of the study is the state of the law as it is in force. The data set is therefore made up of the statutes, case law and contemporary interpretations of these. By relying on these three types of sources, the law for each time frame is assessed comprehensively. However, the data does not include such areas as contractual provisions or collecting societies among others. The focus is instead on the core areas of copyright.[29]

The next section will outline what copyright is and describe two ideal copyright types. The discussion will then move in section three to clarify how these ideal types can be used to measure convergence. Section four presents the results of the analysis, focusing particularly on instances of convergence. The final section will compare these findings with the positions taken in the literature.

2. The Methodology

Policies evolve over time. One concept used to map these kinds of spatial developments is convergence. There is a large body of literature analysing the growing similarity between policies over time, drawn from all areas of policy-making and law.[30] Today, it is generally accepted that convergence refers to the growing similarity over time in respect to a specific policy or institutional design.[31] Three aspects are clear from looking at this definition. First, the temporal dimension is of key importance: convergence describes a process over time and an outcome.[32] Secondly, it focuses on a movement in substantive terms. Some aspect of the policy is moving across a perceived policy space. Thirdly, the term similarity is inherently vague.[33] This means that the policy options and variations have to be defined.

To illustrate what these characteristics mean, let us assume that a policy can have three distinct instruments (A, B and C) in response to an issue. This is the defined policy space. At the first time point, country X uses instrument A while country Y prefers C. Over time (the second time point), both countries change their position and adopt instrument B instead. By amending their law, both of them have changed position in the defined policy space and have moved closer to each other. In summary, convergence is a two-dimensional concept, in which a method must be found to consistently map changes across space over time.

2.1 The Nature of Copyright Policy

To understand the policy space in copyright, it is necessary to understand its major components. Copyright distinguishes between the three categories of works that it protects. The first group focuses on copyrighted works in the traditional sense (hereinafter “CR”). These are protected on the basis of their minimum originality. Examples include literary works, music and art. The second category contains neighbouring rights (hereinafter “NR”). These works are by definition not original and are instead protected because of their economic importance to exploiting a copyrighted work. The core NR are sound recordings and broadcasts. Finally, the third group are performances. Here protection is granted to the actual performance of a work-based on its fixation in a tangible form and further use.

The distinct shape of a copyright policy is determined by a number of characteristics. These features centre on two main areas: the protection of the work (its economic value) and the protection of the author. The combination of economic and author protection, and especially the relationship between them, varies across cultures and can be used to measure convergence in spatial terms.

Economic protection focuses on what is considered a work and how is it protected from unauthorised exploitation. In this area, the distinction is between the copyright owners and the users. First of all, not everything automatically constitutes a work. For CR works, the demarcation is usually drawn on the basis of originality: a minimum threshold must be met. However, NR works and performances do not require such a threshold. Furthermore, once the work is recognised as ‘copyrightable’, other hurdles must be examined, for instance, do any additional formalities have to be complied with in order to secure protection, for example registration or the © symbol? If the work actually benefits from copyright, the focus moves to how strong the protection is and who owns the rights. The relevant features are what kinds of uses need authorisation by the rights owners (economic rights) and which are explicitly exempt (exemptions). In addition, the term of protection and enforcement capabilities (sanctions) also influence the strength of protection. In summary, the first component of copyright policy describes who can benefit, from what kind of protection, in which circumstances.

The second core aspect of copyright policy concerns the relationship between the author and his work. This refers to the authors’ special rights that only he has, and the circumstances under which he can enforce them. This includes specific rights available (moral rights, hereinafter “MR”), the kind of works they apply to, the situations in which they cannot be relied upon (exemptions) as well as the available enforcement capabilities (sanctions). These rights limit the extent to which an author can assign copyright and potentially interfere with the economic exploitability of a work. Therefore, the opposing interested groups in cases of assignment are the copyright owners against the authors of works. In conclusion, the second component of copyright policy emphasises the author’s ability to limit the exploitation of their work. All of these features described above play a significant role in determining the shape of a copyright policy. As a result, this study uses them as indicators later on in the methodology.[34]

2.2 The Structure of Copyright Policy

To examine cultural similarity, a method to identify and conceptualise the differences between copyright systems must be developed. One approach to order the spatial features of copyright (legal culture) is to rely on the theory of legal origin. It distinguishes between two copyright systems in the West: author’s rights systems (“AR”) and common law systems (“CL”). AR is the civil law approach to copyright and prevalent on the European continent. Important examples include Germany and France. CL systems reflect the common law countries’ understanding of copyright. Two major representatives of this system are the US and the UK.

The basic difference between these two systems is how they conceptualise the purpose of copyright: why protection is granted. In common law countries, copyright is based on a mix of two rationales: Utilitarianism and Labour. Utilitarianism provides that protection is granted to ensure that works are created and published. The incentives provided are in the public’s best interest as it facilitates the dissemination of works.[35] In addition, the author deserves protection. This reasoning is based on an interpretation of Locke’s Theory of Labour. The individual uses his resources in the creation of the work and therefore has a right to control it.[36] On the other hand, AR countries protect the personality of the author, which is imprinted on the work.[37] It is therefore not perceived as an incentive to create to benefit the public good, but to protect the author as such.

This difference in rationale affects other core copyright features. Ideal type CL systems emphasise the incentive to disseminate by focusing on the economic exploitability of the work. As a result, rights are owned by the investor; this favours employers over authors because they benefit from the protection and therefore the value of the work. Moral rights to protect the author against these investors are largely absent.[38] Furthermore, any work of value to the public is included. This in turns means that the originality threshold is low and technological works are included, for example sound recordings.[39] At the same time, formalities are considered essential to prevent excessive protection, which has no public value.[40] In addition, protection is not granted to foreigners since their incentive is determined domestically.[41] Economic rights and enforcement provisions designed to benefit the copyright owner are limited to the extent necessary for the dissemination incentive to work. In turn, the exemptions for public benefit uses, for example teaching and libraries are extensive.[42]

In ideal AR systems, the focus is on the author’s personality, which is indistinguishable from the work. His works only benefit from protection if they reflect his personality, necessitating a high originality threshold.[43] This excludes protection for works that are only economically relevant, but not in terms of creativity (NR).[44] At the same time, formalities are absent and protection is also extended to foreigners – the personality does not depend on administrative procedures or citizenship.[45] Since there is no inherent public benefit justification and copyright protection is viewed as a right rather than a grant, economic rights are extensive and the exemptions very limited. Furthermore, they tend to include some kind of remuneration for the author.[46] Finally, the investor is in a weak position as strong MR and primary ownership rules both benefit the author at the expense of an investor.[47]

The section summarised the two different approaches to copyright: AR and CL. Based on these descriptions, eleven distinct areas or dimensions can be identified in which these two systems are expected to vary. Therefore, each of these dimensions reflects an established difference between AR and CL systems. These dimensions are set out in the table below. For example, AR and CL systems vary significantly on the level of originality required for protection.

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

Table 1: The individual dimensions describing the systematic differences between AR and CL copyright systems.

Although these differences clearly establish two distinct copyright systems in their ideal form, they are too vague to be quantifiable. Therefore, specific indicators need to be selected for each of these individual dimensions. The term ‘indicators’ here refers to those identifable features of a policy that determine its characteristics, as describes in sections 2.1 and 2.2.[48] For example, the “Emphasis of Protection” refers to the comparative strength between economic and moral rights. This means that the features defining both areas have to be combined. To determine the strength of economic provisions, it is first necessary to identify how a work can benefit from protection. In terms of indicators, the number of work types in combination with the number and impact of formalities provides this information. In addition, the strength of economic protection also depends on the substantive strength of the provisions. This can be assesed by using the number of economic rights, their term of protection, the exemptions which apply to them (both the number and average number of conditions) and the number of sanctions for economic works must be considered. For moral rights, their number, term of protection, applicable exemptions and sanctions are relevant.