1 Introduction

Over the years, the fashion industry has expended substantial time and resources in efforts to disrupt the activities of counterfeiters, viewed as a serious threat to its continuing viability. In 2017, according to the Global Brand Counterfeiting Report 2018 (GBCR),[1] global sales of counterfeit products amounted to 1.2 trillion USD, and losses attributable to fake luxury goods sold online alone were estimated at $32 billion. The fakes were becoming so difficult to distinguish from the original that sometimes “only the manufacturer … [could] make out the difference between the original and the fake”.[2] In response, fashion brand owners began experimenting with a range of technologies of authentication, from nanotechnology, to the Internet of Things, to AI, to blockchain – finding use for a distributed ledger technology that claimed the ability to effectively “automat[e] trust”, offering “an authoritative and secure source [of authentication information] for all participants in a supply chain”.[3]

But the experiments around the use of blockchain did not stop there. Now being considered is a further prospective use of the technology as an authoritative and secure source of public information about provenance,[4] addressing another problem that has dogged fashion in recent years – namely public concerns about industry safety standards, labour practices and environmental impact of fashion production and use, responding to scandals widely reported in the media and generally acknowledging that “[a] new global ethos is emerging, and billions of people are using consumption as a means to express their deeply-held beliefs”,[5] with “intensifying discussions … around materialism, over-consumption and irresponsible business practices”.[6] Here we see the imaginary of blockchain as a mechanism of public transparency for ethical and sustainable fashion becoming aligned to a wider discourse of the public‘s right to know. This is evoked to counter “control of knowledge, inscrutability, ignorance, and deceit in the service of the powerful” and insist on greater accountability.[7]

Already work has begun on promoting blockchain’s favourable features as a technology of radical transparency. As LVMH puts it, spruiking its Aura blockchain in 2019, “[t]he benefits for customers are increased transparency and enhanced ethical products”, as “every step of the item’s life cycle is registered [on the digital ledger] … from raw materials to the manipulation of them through dyeing, weaving and tanning, manufacturing and shipping”, making these part of the “conversation” with “the discerning consumer”.[8] In 2020, French blockchain platform lablaco and The Global Fashion Exchange launched The SwapChain with a mission “to make a global and measurable target of recirculating 100,000 items in the next 12 months, contributing towards the attainment of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals”.[9] And the UN Economic Commission for Europe announced its own pilot project for blockchain-enabled “sustainable value chains”.[10] In such vignettes, Leanne Kemp observes[11] we see the supply chain being recast as a “value chain”, supported by blockchain. “Instead of a static linear diagram on a page” customers are presented with “a textured story full of human and physical detail … show[ing] the who, where and how in high definition”, arguing that “by making the past come alive, provenance can play a dynamic role in the present, and also reach into the future”.

As such, blockchain appears to be moving into an interesting phase of its short tumultuous existence. In another context, Nancy Baym, Lana Swartz, and Andrea Alarcon have argued that blockchain is taking on the character of a “convening technology”,[12] drawing on the earlier work of Clive Barnett on convening publics as sites of public discourse and action.[13] Barnett anticipated in 2008 that “pre-existing infrastructures of communication and circulation” can take on a convening function,[14] and that “[r]ather than modelling public space on the idea of gathering and assembly in the presence of others, we should look at the ways in which publics are convened through practices of dissemination, dispersal and scattering”.[15] A decade later Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon added a concrete example, pointing to blockchain’s public-facing decentralised infrastructure and public discourse of music sharing as allowing the technology to take on a convening function; serving as “the focus of a conversation that can [potentially] address issues far beyond what it may ultimately be able to address itself”, marshalling “resources, institutions and other forms of power”.[16] In the next section of this article, we suggest that blockchain is taking on a similar role with respect to fashion. It is offering itself as a “chance to reset and completely reshape the industry’s value chain — not to mention an opportunity to reassess the values by which we measure our actions” – with “themes of digital acceleration … and corporate innovation” radically prioritised.[17]

Indeed, there are several reasons to expect that what Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon have to say about music can be applied, in large part, to fashion which, like music, is a means of expression that can be relied on to speak out on social issues ranging from anti-slavery, global warming, racial inequality, excessive consumerism, and coordination on wearing face masks in times of pandemic.[18] As such, fashion – in attempting to deal with its own social issues, including public perceptions of control of knowledge, inscrutability, ignorance, and deceit in the service of the powerful, along with a broader range of issues – can benefit from blockchain’s ability to function as a convening technology that brings together loosely aligned individuals and groups for public good ends and foments public discussions around issues of social importance. A difficulty is reconciling this beneficial function with industry as well as public demands for the so-called “technology of trust”[19] to be rendered trustworthy in practice through the introduction of an effective governance model.

2 Blockchain technology

Blockchain technology has been operational for more a decade without any great attention being paid to governance outside that offered by the architecture. Touted as a cryptographic solution to the top-down bureaucracy of the financial industry, eliminating the need for reconciliation and intermediation and enabling direct transactions between traders.[20] It was designed as (a) a distributed technology, allowing participants to “continuously trace their assets and settle transactions autonomously”, and (b) a secure model that, based on a sequence of interlocking blocks requiring cryptographic processes of validation, was “fault-tolerant, resilient, and permanently available”.[21] In the context of financial transactions the second feature has been most emphasised. In the words of Antony Lewis, founder of Bits on Blockchain, the logic is “confirm as you go” rather than “confirm after the fact”.[22] And, with a cyber-libertarian ethos underpinning the blockchain, there was little need for governance beyond that imposed by the technology. Note, even that may be changing now as cryptocurrencies become more mainstream.[23] But as blockchain spreads into the creative industries such as music, art, and now fashion, the second feature has not gone away.[24] The ability of blockchain conferring to coordinate activities between strangers with diverse values and expectations is becoming more interesting.[25]

Music and art provide early case studies. As Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon explain in relation to music, notwithstanding the rather limited technological achievements to date of blockchain in providing concrete results in building ongoing registers of music metadata,[26] in line with early utopian aspirations of creating “the universal, authoritative reservoir for these types of information” that “would be open to and accessible by anyone”.[27] What is striking is how “[e]ntrepreneurs, activists, and others have created start-ups, working groups, workshops, hackathons, and conferences to understand what blockchain is and how it might solve problems in an enormous and expanding range of domains”.[28] This shows “blockchain, as an only almost-ready technology, served as a focus to bring diverse actors together as a sonic public striving to collaboratively reshape infrastructures”.[29] Martin Zeilinger, whose ethnographical study of digital art as “monetised graphic” is cited by Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon, notes that debates may also extend to deeper questions about the meaning of “art”, the nature of authorship, and problems with intellectual property rights.[30] While the authors do not go into the reasons for such discursive dimensions and detours, we can speculate that they reflect, to an extent, the cultural dimension of entertainment. In the words of Jon Garon: “Entertainment is unlike any other industry. It is not culturally mediated; rather it is the medium of culture” and it often leads “public debate on fundamental notions of economic and moral justice”.[31]

Now we see blockchain positioning itself in the fashion industry, bringing diverse actors together as the public strives to reshape the infrastructures of ethical and sustainable fashion, and at the same time engage with deeper questions about the human, cultural and social values (but not only in relation to fashion). Again, we can speculate that these functions reflect the specific cultural and discursive dimension of fashion.[32] As Fred Davis puts it, “people communicate some things about their persons” through fashion.[33] Moreover, the process of construction and negotiation is reflexive, with “individuals monitor[ing] the world around them and chang[ing] their behaviour in light of incoming information”,[34] navigating between their twin desires to present as individuals and to affiliate with social groups.[35] This influence can work the other way as well, i.e. individuals affecting the world around them (individually or collectively). For instance teen activist Greta Thunberg inspiring “ecoethic” fashion,[36] and social media influencers donning face masks in a bid to encourage others to follow.[37] This constant process of human identity being continually shaped in light of incoming information, and in turn shaping information, makes fashion attuned to blockchain’s promise of a transparent ongoing iterative record of “information about changes to [fashion] identities that moves through time”,[38] accompanied by a wider discourse centred on their contributions to broader social change.

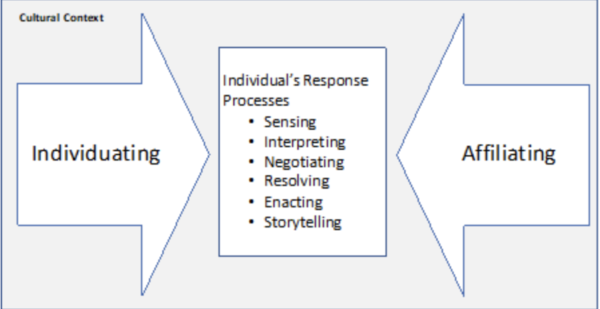

Figure 1 shows this iterative process of possible responses that individuals may have to such pressures. The right-hand side depicts the pressure to affiliate with social groups in expressing social values and choices about, for instance, ethical and sustainable fashion. The left-hand side depicts the pressure to stand out from others as an individual, reflecting and expressing personal values. In the middle, we see the possible responses whereby individual and social values become (to an extent) reconciled through processes such as sensing, interpreting, negotiating, resolving, enacting and storytelling.[39]

Nevertheless, it cannot be assumed that the process of social change will be speedy or even in one direction under the influence of social norms. To begin with, social norms themselves may have limited influence. Pricing and demands for ever-changing styles may have more impact on actual decisions, at least in the short-term. Even where support is expressed for ethical and sustainable fashion in response to questions in surveys – as with 31% of Gen Z and 26% of Millennials in the US “stat[ing] that they will pay more for products that have the least negative impact on the environment”,[40] these preferences are not always reflected immediately in purchasing behaviours.[41] These norms may also operate in conflict. Different social groups may express different social values, imposing conflicting pressures on individuals which need to be resolved – as with anti-mask social movements,[42] vegan ethical fashion versus sustainable fashion.[43] Indeed, seeking to put all this data on a blockchain may simply highlight conflicts rather than facilitating strong social consensus, although having a shared record of the debates might also be beneficial.

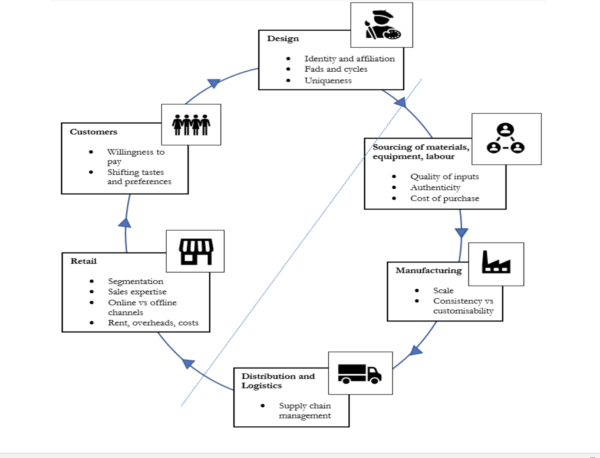

The fractured nature of the industry is a further complicating factor. Figure 2 shows the range of those involved in the fashion industry cycle.[44] Several large players exist, in sourcing, manufacturing and distribution/logistics activities benefiting from their organisational capacities and economies of scale. Their activities are supplemented by those of numerous designers, pattern makers, seamsters and other fabricators of fashion, boutiques and specialists and a stream of emerging talent. Individual designers may seek to influence social values to fit with their personal values, as with Martina Spetlova’s 2019 Fashion Week MWoven collection emphasising ethical handmade bags and jackets and showcasing her integration of Provenance’s blockchain technology platform.[45] Stella McCartney’s 2019 advertising campaign, partnering with members of Extinction Rebellion aimed to raise awareness of climate change.[46] Others may seek to pursue individual projects, for instance participating in the sewing and crafting movement with its emphasis on sustainable fabrics, re-use, indie patterns, and home-production rather than industry-based fabrication.[47] And economic pressure for cheap fashion that pays little attention to ethical and sustainability values still play a significant role in fashion markets, and given the economically restricted circumstances of many people’s lives will likely continue to do so.

Fashion firms contemplating incorporation of blockchain applications into their business models are subject to their own business and ethical constraints; including their own ideas about how the so-called “technology of trust” might affect their business activities. As detailed in Table 1, difficult choices may be required between different types of blockchain – with some coming closer to the original conception of a public blockchain while others fall at the other end of the spectrum as more like a technologically-enhanced form of a private database.

Table 1: Trade-offs between Private, Shared and Public Blockchain Registers for Fashion

| Private | Shared | Public* | |

| Efficiency | |||

| Speed of transactions | Very fast | Fast | Slow |

| Energy use | Low | Medium | High |

| Cost to firm/s of building, maintaining | High | Medium | Low |

| Importance of critical mass in ecosystem | Low | High | Very high |

| Trust and Engagement | |||

| Degree of trust in the blockchain technology | Low | Medium | High |

| Degree of trust in the inputted data | High | Medium | Low |

| Amenability to public discussion (convening) | Low | Medium | High (but with issues) |

* Hybrid versions are also emerging, such as the “public permissioned” blockchain (eg IBM Hyperledger Fabric) which is public in the sense that the public can freely read it, but private or shared in the sense that only permitted parties are entitled to write: i.e. not a public blockchain in the full sense. Alternatively, this type may be termed a “private and open” blockchain.[48] Such hybrid options are among the newest types of blockchain and still under development.

A fashion firm may note that the speed of transactions and energy efficiency will be significantly greater for a private or shared blockchain than for a public blockchain. These may be crucial considerations. Indeed, a firm which is highly geared to customers’ preferences for ethical and especially sustainable fashion (rather than focusing on minimising costs) will appreciate the difficulty of embracing a public blockchain if the underlying technology is highly energy inefficient with dubious impacts on sustainability. Although some experts posit that “alternative blockchain solutions with significantly lower power consumption are starting to become available, and promising concepts are being tested that could further reduce the power consumption of large blockchain networks in the near future”.[49] Although the expense involved in building and maintaining a private blockchain may point a firm away from that solution, a better opportunity may arise from shared platforms, possibly employing open source software, where the platform construction and maintenance costs can be spread across multiple users rather than moving to a fully public blockchain solution. Both small and large firms may find some benefit from the network effects gained by joining forces in coordination of building and operating new fashion ecosystems.[50] The efforts associated with building and maintaining critical mass explain why IBM is a leader among the platform providers,[51] and why LVMH has opted to collaborate with ConSensys and Microsoft to build a shared platform that can be used across the industry rather than kept for its exclusive use.[52]

Another fundamental trade-off exists with regards to trust in the technology versus trust in the firm or firms involved in providing, participating in, and overseeing its operation (see Table 1). Some businesses may consider that the difficulty of editing or retracting information once committed to a public blockchain makes immutability a key advantage of this type of blockchain. Security may also be seen as a credible commitment for this type due to the cryptographic techniques used to encode the data and ensure it is not altered. At present, public blockchain is still judged “extremely secure though not unbreakable”.[53] These signals of credibility are weaker for a shared blockchain and are potentially absent for a private blockchain. In short, those opting for a private blockchain must trust the firm’s (or firms’) management and brand, rather than rely upon the technology per se to provide trust. [54] A shared platform entails its own risks of having to trust in, and coordinate with, partners. However, there may be other dimensions as well to the “trust equation” – for instance, there may be concerns as to whether data recorded on a public blockchain, involving diverse uncoordinated actors, can be fully trusted over time (example of the collective action problem). It may be that certain techniques, e.g., of peer-to-peer monitoring, can be devised to address the challenges of ensuring accurate inputted data.[55] But so far most of those techniques, for instance investing resources in checking inputted data, editable blockchains,[56] blocked access,[57] and flagging errors,[58] are currently more feasible for private or shared blockchains than for public blockchains. For a fashion firm considering the choice between a public versus a private or shared blockchain, a key question is whether the increase in trust to be gained from opting for the immutability of a public blockchain is sufficient to offset the possibly substantial decrease in trust regarding the quality of the inputted data. Indeed, if the aim of the firm is to assure consumers that standards of ethical or sustainable fashion are met, this may point away from public blockchain in a practical sense.

Another issue that further complicates the assessment is the question of the firm’s interest in engaging in public discussion. Here we come back to the convening function. As Claus Dierksmeier and Peter Seele point out,[59] firms which see their role as entailing “a responsibility to engage in open discourse, to allow for societal participation and to contribute to the closing of regulatory gaps” may find advantages in adopting an ethos of “data deliberation”.[60] Whereby relevant stakeholders “join forces to increase public goods and encounter challenges such as environmental system risks”.[61] And, if so,

for blockchain technology, in particular with a view to improved transparency in supply chain management, something similar might hold. If blockchain technology is used to support a more open digital environment, it may well boost forms of responsible digitalization, since the specifics of distributed ledger registries allow for better structured data, not in the least when it comes to open access solutions.[62]

This factor would seem to point in favour of a public versus a private or shared blockchain and thus it may lead in a different direction to the decisional factor regarding trust (especially if trust in the data is important, as we have noted above). Ways need to be found to overcome this practical tension between the ability to trust the data and the convening function – although we add that ultimately even the convening function may be undermined if publics become unable to trust the data they seek to draw on in support of their positions.[63]

3 Law as a trust mechanism

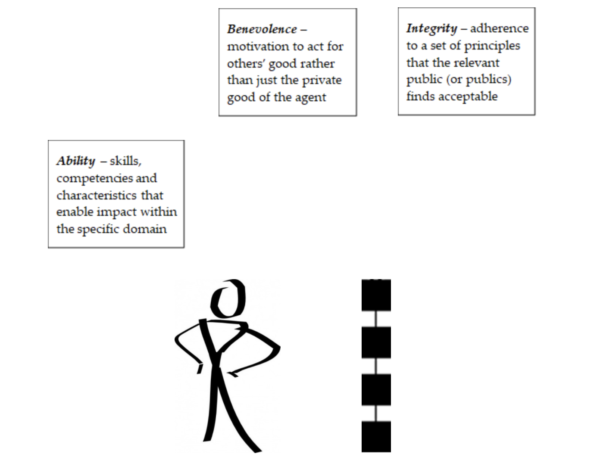

Here we see a role for law in not just governing blockchain but governing with the specific purpose of engendering and supporting public trust in the veracity of the data while at the same time ensuring that trust is not misplaced, i.e., the law’s purpose is to ensure that technologies and practices are trustworthy in the recognised sense of meeting minimal standards of ability, benevolence and integrity, as visualised in figure 3 below.[64]

To an extent, law may already be geared to trustworthiness including with respect to fashion. For instance, trademark law may underpin the legality of certification labels deployed to certify that prescribed standards are met for ethical and sustainable fashion.[66] Modern slavery law may require companies to declare steps taken to address slavery practices in their operations,[67] and allowing those affected by practices to bring claims.[68] Unfair competition laws may proscribe unfair or deceptive conduct.[69] Whether these laws work well is another question. For example, the 2020 Boohoo factory scandal in Leicester (with a review confirming that allegations about dangerous conditions and low pay in the factory workers’ conditions were “substantially true”)[70] shows that even with a Modern Slavery Act there may be little effort by firms to investigate and act on unethical labour practices in their supply chains.[71] The Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh in 2013 also demonstrates the inadequacies of trademark law including its certification systems in ensuring that claimed standards are met.[72]

More could be done to ensure that regulation takes into account the exigencies of blockchain in order that its technological affordances and safeguards are complemented by “adequate internal governance structures and clear external accountability”, all contributing to trustworthiness and trust.[73] Indeed, law may go further in insisting on the development of technological affordances and safeguards – such as the hybrid models noted above, which combine public facing blockchains with private controls over the quality of the data inputted.[74] For instance, supply chain transparency laws could mandate reporting using publicly accessible digital platforms, as part of “a radical shift towards public transparency and accountability, underpinned by evidence”.[75] Likewise, there could be more rigorous coordination in regulatory processes involving standards organisations and certification bodies authorised to ensure ethical and sustainability standards are met in the deployment of blockchain.[76]

Of course, law comes with its own constraints. As Niezen points out,

[i]t is when we combine the effects of technologies of communication with technologies of law that the new era of justice claims and campaigns comes into sharper focus … Law seeks (though it rarely finds) certainty and finality and will even distort reality to achieve it.[77]

Thus, in the largely unchartered space of blockchain regulation, as Karen Yeung argues, the onus is on lawmakers to seek out “creative and practically effective ways for exerting their authority over activities upon, and associated with, blockchain networks”.[78] At the same time, those subject to law’s regulation may fairly argue that regulators in this space should move away from the mindset that they need to be “overpowering”, in favour of becoming more “constructive and educational”.[79] They should also be working closely with relevant actors to achieve desired results and to test the feasibility of the solutions being considered. One way, we suggest, would be to deploy the logic of blockchain as a convening technology with policymakers drawing on the authority and experience of a multiplicity of growers, producers, workers, designers, firms, platform providers, consumers, along with all other individuals and groups whose rights, freedoms and interests are at stake. In the words of Christine Parker and Fiona Haines, engaging in “ongoing interactions (contests, conflicts, alliances, modelling, and mimicry) between networks of multiple actors at multiple levels (local, national, and global; and within and between agencies and organizations at each of these levels)”.[80] At the same time, if education is key to the ability of policymakers to effectively regulate unchartered spheres such as blockchain, equally education is a key consideration for stakeholders who are seeking to make a meaningful contribution in regulatory processes. Here, as elsewhere, the value of participation depends on the ability of participants to receive, impart and assess information and ideas (i.e. to exercise the right to know).[81] In short, access to relevant data, along with the tools necessary to evaluable its veracity and value, is a first step to humans becoming productively involved in assessing problems, engaging in debates and seeking legal (as other) solutions.[82] And a key task for policymakers is to ensure that sufficient attention is paid to all these dimensions.

5 Conclusion

In this article, we have posited that blockchain has transcended its cryptocurrency origins in offering the fashion industry and its diverse publics the enticing prospect of a transparent value chain for ethical and sustainable fashion, catering to public demands for a right to know data on authenticity and provenance. Whether this is a feasible prospect remains to be seen. Nevertheless, in staking out its position, blockchain appears to be moving into an interesting phase of its short tumultuous existence, taking on the character of a “convening technology” and becoming, in the words of Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon, “the focus of a conversation that can [potentially] address issues far beyond what it may ultimately be able to address itself”, and marshalling “resources, institutions and other forms of power”.[83] A difficulty is reconciling this beneficial function with the need to be trustworthy in practice, requiring at least a minimal governance model. Therefore, we have sought to set out some desirable parameters for such governance. In the final scheme of things, blockchain may become a transformative technology for ethical and sustainable fashion, delivering major economic and social value.[84] But a great deal rides on the abilities and readiness of a wide variety of stakeholders – including designers, firms, platform providers, publics, and policymakers – to navigate the challenges.

[1] Global Brand Counterfeiting Report, 2018 (ResearchAndMarkets.com, December 2017), available at https://www.researchandmarkets.com/research/dctz2p/global_brand?w=12 (accessed 25 July 2020).

[2] T. N. Ashtok, “World of Counterfeits” (The Statesman, 22 June 2020), available at https://www.researchandmarkets.com/research/dctz2p/global_brand?w=12 (accessed 25 June 2020).

[3] “Blockchain’s Real Promise: Automating Trust” (MIT Technology Review, 13 June 2019), available at https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/06/13/102979/blockchains-real-promise-automating-trust/ (accessed 25 June 2020).

[4] Alexis Bateman and Leonardo Bonanni, “What Supply Chain Transparency Really Means” (Harvard Business Review, 20 August 2019), available at https://hbr.org/2019/08/what-supply-chain-transparency-really-means (accessed 25 July 2020). See also Steve New, “The Transparent Supply Chain” (2010) 88/10 Harvard Business Review 76-82.

[5] The State of Fashion 2019 (BOF and McKinsey & Co, 2019), available at https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-state-of-fashion-2019-a-year-of-awakening (accessed 27 July 2020), p. 445. See also The State of Fashion 2020 (BOF and McKinsey & Co, 2020), available at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/The%20state%20of%20fashion%202020%20Navigating%20uncertainty/The-State-of-Fashion-2020-final.pdf (accessed 27 July 2020); The State of Fashion 2020: Coronavirus Update (BOF and McKinsey & Co, 2020), available at http://cdn.businessoffashion.com/reports/The_State_of_Fashion_2020_Coronavirus_Update.pdf?int_source=article2&int_medium=download-cta&int_campaign=sof-cv19 (accessed 18 August 2020), The State of Fashion 2021 (BOF and McKinsey & Co, 2021), available at https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/state-of-fashion (accessed 21 September 2021).

[6] The State of Fashion 2020: Coronavirus Update, supra n. 5, pp. 18-19.

[7] See Ronald Niezen, #HumanRights: The Technologies and Politics of Justice Claims in Practice, (Stanford University Press, 2020), p. 190.

[8] Alice Newbold, “Louis Vuitton to Launch First Blockchain to Help Authenticate Luxury Goods” (Vogue, 17 May 2019).

[9] Roddy Clarke, “Global Fashion Exchange Launches New Digital Swapping System” (Forbes, 27 May 2020), available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/roddyclarke/2020/05/27/global-fashion-exchange-launches-new-digital-swapping-platform/#279006796df1 (accessed 26 July 2020).

[10] “Enhancing Transparency and Traceability of Sustainable Value Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector – Pilot Project Document Implementing a blockchain technology for traceability and due diligence in the cotton value chain in support of a circular economy” (UNECE, 20 April 2020), available at https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trade/SustainableTextile/2020_April_Webex/Blockchain_Pilot_Project_Doc_and_Progress_20April2020.pdf (accessed 26 July 2020).

[11] Leanne Kemp, “How Can E-Provenance Transform Supply Chains Into Value Chains?” (Forbes, 16 March 2020), available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/leannekemp/2020/03/16/how-can-e-provenance-transform-supply-chains-into-value-chains/#318475ed128f (accessed 26 July 2020).

[12] Nancy Baym, Lana Swartz, Andrea Alarcon, “Convening Technologies: Blockchain and the Music Industry” (2019) 13 International Journal of Communication 402–421.

[13] Clive Barnett, “Convening Publics: The Parasitical Spaces of Public Action”, in Kevin R. Cox, Murray Low, and Jennifer Robinson (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Geography (London, UK: Sage, 2008), 403-418.

[14] Ibid., p. 411.

[15] Ibid., p. 416.

[16] Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon, supra n. 12, p. 403.

[17] The State of Fashion 2020: Coronavirus Update, supra n. 5, p. 8.

[18] See Julya Kros, “20 Fashion Brands Getting Most Creative With Coronavirus Face Masks” (Forbes, 27 April 2020), available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/stephanrabimov/2020/04/27/20-fashion-brands-getting-most-creative-with-coronavirus-face-masks/#819cf2475995 (accessed 18 August 2020).

[19] Chris Berg, Sinclair Davidson, and Jason Potts, How to Understand the Blockchain Economy: Introducing Institutional Cryptoeconomics (Edward Elgar, 2019), p. 2.

[20] See Benjamin Wallace, “The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin” (Wired, 23 November 2011), available at https://www.wired.com/2011/11/mf-bitcoin/ (accessed 3 August 2020).

[21] Jörg Weking et al., “The Impact of Blockchain Technology on Business Models – A Taxonomy and Archetypal Patterns” (2020) 30 Electronic Markets 285-305.

[22] Antony Lewis, “Avoiding Blockchain for Blockchain’s Sake: Three Real Use Case Criteria” (Bits on Blocks, 24 July 2017), available at https://bitsonblocks.net/2017/07/24/avoiding-blockchain-for-blockchains-sake-three-real-use-case-criteria/ (accessed 27 July 2020).

[23] See Primavera de Filippi, “Bitcoin: A Regulatory Nightmare to a Libertarian Dream” (2014) 3 Internet Policy Review 1-11.

[24] Marie Malaurie-Vignal, “Blockchain, Intellectual Property and Fashion” (2020) 15 Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice 92-97.

[25] Ellie Rennie, “The Challenges of Distributed Administrative Systems” (2020) 66 Australian Humanities Review 233-239.

[26] Although see António Madeira, “Blockchain to Disrupt Music Industry and Make It Change Tune” (Cointelegraph, 6 June 2020), available at https://cointelegraph.com/news/blockchain-to-disrupt-music-industry-and-make-it-change-tune (accessed 4 August 2020).

[27] D. A. Wallach, “Bitcoin for Rockstars” (Wired, 10 December 2014), available at https://www.wired.com/2014/12/bitcoin-for-rockstars/ (accessed 27 July 2020).

[28] Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon, supra n. 12, p. 403.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Martin Zeilinger, “Digital Art as ‘Monetised Graphics’: Enforcing Intellectual Property on the Blockchain” (2018) 31(1) Philosophy and Technology 15-41. Cf Andrew Chow, “NFTs Are Shaking Up the Art World – But They Could Change So Much More” (Time, 22 March 2021), available at https://time.com/5947720/nft-art/ (accessed 22 July 2021).

[31] Jon Garon, “Towards a Conceptual Framework of Entertainment Law for the Twenty-First Century” (SSRN, 2 May 2020), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3591236 (accessed 2 August 2020), p. 3; Jon Garon, “Entertainment Law” (2012) 76 Tulane Law Review 559-672, p. 562.

[32] See Georg Simmel, “Fashion” in Donald N. Levine (ed.), Georg Simmel on Individuality and Social Forms (University of Chicago Press, 1971), 294-323; Roland Barthes, The Fashion System (transl Matthew Ward and Richard Howard, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990).

[33] Fred Davis, Fashion, Culture, and Identity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 4; Craig J. Thompson and Diana L. Haytko, “Speaking of Fashion: Consumers’ Uses of Fashion Discourses and the Appropriation of Countervailing Cultural Meanings” (1997) 24 Journal of Consumer Research 15-42.

[34] Daniel Chaffee, “Reflexive Identities”, in Anthony Elliott (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Identity Studies (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 100.

[35] See Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (London, Allen Lane, 1969); Susan B. Kaiser, Fashion and Cultural Studies (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012); Sangah Song, Heechong Lee, and Kyulim Kim, “Who Says What to Wear? Examining Tensions between Conformity and Individuality” in Eunju Ko and Arch G. Woodside (eds.), Luxury Fashion and Culture (UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2013), pp. 101-128.

[36] Vicki Hallett, “Teen Activist Greta Thunberg is Now a Fashion Icon, Whether She Likes It Or Not” (Washington Post, 14 April 2020), available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/teen-activist-greta-thunberg-is-now-a-fashion-icon-whether-she-likes-it-or-not/2020/04/13/833ce1fe-6d33-11ea-aa80-c2470c6b2034_story.html (accessed 27 July 2020).

[37] “How is the Mask Trend Behaving on Social Media?” (heuritech, 16 July 2020), available at https://www.heuritech.com/blog/articles/masks-trend-social-media/ (accessed 27 July 2020).

[38] Berg, Davidson, and Potts, supra n. 19, p. 110.

[39] Song, Lee, and Kim, supra n. 34.

[40] The State of Fashion 2020, supra n. 5, p. 55.

[41] See Timothy M. Devinney, Pat Auger, and Giana Eckhardt, The Myth of the Ethical Consumer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[42] See Lauren Aratani, “How Did Face Masks Become a Political Issue in America?” (The Guardian, 29 June 2020), available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/29/face-masks-us-politics-coronavirus (accessed 2 August 2020); Kiona N. Smith, “Protesting During A Pandemic Isn’t New: Meet The Anti-Mask League Of 1918” (Forbes, 29 April 2020), available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/kionasmith/2020/04/29/protesting-during-a-pandemic-isnt-new-meet-the-anti-mask-league/#7a88ee2212f9 (accessed 2 August 2020).

[43] Regina Henkel, “Vegan vs Animal-based Fashion: Which One is More Sustainable?” (FashionUnited, 25 February 2019), available at https://fashionunited.uk/news/fashion/vegan-vs-animal-based-fashion-which-one-is-more-sustainable/2019022541758 (accessed 2 August 2020).

[44] See The State of Fashion 2020: Coronavirus Update, supra n. 5, p. 14.

[45] Sarah Fulton Vachon, “Fashion Week: Bring More than Transparency – Bring Integrity” (Provancenews, 13 September 2019), available at https://www.provenance.org/news/movement/fashion-week-bring-more-than-transparency-bring-integrity (accessed 2 August 2020).

[46] Brooke Kushwaha, “Winter 2019 Ad Campaign Puts Climate Change at the Forefront” (L’Officiel, 30 July 2019), available at https://www.lofficielusa.com/fashion/stella-mccartney-winter-2019-ad-campaign-puts-climate-change-at-the-forefront (accessed 2 August 2020). McCartney is an eco-ethical partner in the UNECE Pilot Project: “Enhancing Transparency and Traceability of Sustainable Value Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector”, supra n. 10.

[47] See Gretchen Brown, “Is DIY the Future of Ethical and Sustainable Fashion?” (Rewire, 12 June 2020), available at https://www.rewire.org/diy-ethical-sustainable-fashion/ (accessed 22 July 2021.

[48] See Juan José Bullón Pérez et al., “Traceability of Ready-to-Wear Clothing Through Blockchain Technology” (2020) 12 Sustainability 1-21, p. 4.

[49] Johannes Sedlmeir et al., “Recent Developments in Blockchain Technology and their Impact on Energy Consumption”, (2021) arXiv:2102.07886 [cs.CR] (translated version of a German article published in Informatik Spektrum), available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.07886 (accessed 21 July 2021). See also Johannes Sedlmeir et al., “The Energy Consumption of Blockchain Technology: Beyond Myth” (2020) 62 Business & Information Systems Engineering 599-608.

[50] See Marco Iansiti and Karim R. Lakhani, “The Truth About Blockchain” (2017) Harvard Business Review 119-128; Michael Cusumano, Annabelle Gawer, and David B. Yoffie, The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power (New York: Harper Business, 2019).

[51] Vishal Chawla, “IBM Blockchain: How Big Blue Is Using Distributed Ledgers To Dominate Global Supply Chains” (Analytics India Magazine, 8 September 2019), available at https://analyticsindiamag.com/ibm-blockchain-supply-chain/ (accessed 3 August 2020).

[52] See “LVMH, ConsenSys and Microsoft Announce AURA, A Consortium to Power the Luxury Industry with Blockchain Technology” (ConsenSys, 16 May 2019), available at https://consensys.net/blog/press-release/lvmh-microsoft-consensys-announce-aura-to-power-luxury-industry (accessed 25 July 2020).

[53] Cusumano, Gawer, and Yoffie, supra n. 49, p. 9.

[54] Berg, Davidson, and Potts, supra n. 19, pp. 29-30.

[55] See David Rozas, Antonio Tenorio-Fornés, and Samer Hassan, “Analysis of the Potentials of Blockchain for the Governance of Global Digital Commons” (Frontiers in Blockchain, 28 April 2021), available at https://doi.org/10.3389/fbloc.2021.577680 (accessed 21 July 2021).

[56] See Giuseppe Ateniese et al., “Redactable Blockchain – or – Rewriting History in Bitcoin and Friends” 2017 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), pp. 111-126; Joshua Althauser, “Accenture Secures Patent for Its ‘Editable Blockchain’ Technology” (Cointelegraph, 29 September 2017), available at https://cointelegraph.com/news/accenture-secures-patent-for-its-editable-blockchain-technology (accessed 6 August 2020).

[57] See Silvan Jongerius, “GDPR’s Right to be Forgotten in Blockchain: It’s Not Black and White” (Tech GDPR, 13 August 2019), available at https://techgdpr.com/blog/gdpr-right-to-be-forgotten-blockchain/ (accessed 6 August 2020).

[58] See Mike Murphy, “Who is Buying into IBM’s Blockchain Dreams?” (Protocol, 9 March 2020), available at https://www.protocol.com/ibm-blockchain-supply-produce-coffee (accessed 6 August 2020).

[59] Claus Dierksmeier and Peter Seele, “Blockchain and Business Ethics” (2020) 29 Business Ethics: A European Review 348-359.

[60] Citing Mario D Schultz and Peter Seele, “Conceptualizing Data-Deliberation: The Starry Sky Beetle, Environmental System Risk, and Habermasian CSR in the Digital Age” (2020) 29 Business Ethics: A European Review 303–313.

[61] Dierksmeier and Seele, supra n. 58, p. 356.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Cf Niezen, supra n. 7, p. 204.

[64] See Roger C. Mayer, James H. Davis and F. David Schoorman, “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust” (1995) 20 The Academy of Management Review 709-734; Balázs Bodó, “Mediated Trust: A Theoretical Framework to Address the Trustworthiness of Technological Trust Mediators” (2020) New Media & Society 1-23.

[65] Factors adapted from Mayer, Davis and Schoorman, “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust”; human and blockchain images derived from http://clipart-library.com/clipart/pcqrMpeRi.htm (accessed 8 February 2022; licensed for personal use) and adapted from https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/File:Blockchain.png (Theymos, CC-BY 3.0 licence).

[66] As to which, see Margaret Chon, “Marks and More(s): Certification in Global Value Chains”, in Irene Calboli and Edward Lee (eds), Trademark Protection and Territoriality Challenges in a Global Economy (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2014) pp. 79-99; Graeme W. Austin, “Anglo and E.U. Frameworks for Certification and Collective Trade Marks”, in Jane C. Ginsburg and Irene Calboli (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of International and Comparative Trademark Law (Cambridge University Press, 2020) pp. 296-307.

[67] For instance, California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010; Modern Slavery Act 2015 (UK); Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth). See Vadim Chaban, “What is the State of Law for Companies When it Comes to Modern Slavery?” (The Fashion Law, 14 July 2020), available at https://www.thefashionlaw.com/what-is-the-state-of-the-law-when-it-comes-to-companies-and-modern-slavery/ (accessed 24 August 2020).

[68] For instance, U.S Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2020, 22 U.S. Code § 7101 et seq. See Fabio Leonardi, “What a Modern Slavery Law Means for the Fashion Industry” (The Fashion Law, 16 March 2020), available at https://www.thefashionlaw.com/what-a-modern-slavery-law-means-for-the-fashion-industry/ (accessed 24 August 2020).

[69] Dirk A Zetzsche, Ross P Buckley, and Douglas W Arner, “The Distributed Liability of Distributed Ledgers: Legal Risks of Blockchain” (2018) University of Illinois Law Review 1361-1406.

[70] See Archie Bland and Kalyeena Makortoff, “Boohoo Knew of Leicester Factory Failings, Says Report” (The Guardian, 26 September 2020), available at https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/sep/25/boohoo-report-reveals-factory-fire-risk-among-supply-chain-failings (accessed 21 July 2021); Alison Levitt QC, “Independent Review Into the Boohoo Group PLC’s Leicester Supply Chain” (24 September 2020), available at https://www.boohooplc.com/sites/boohoo-corp/files/final-report-open-version-24.9.2020.pdf (accessed 21 July 2021).

[71] See Jessi Baker MBE, “The Boohoo Scandal Shouldn’t Shock Anyone — Modern Slavery is a Pandemic” (CitiA.M., 20 July 2020), available at https://www.cityam.com/the-boohoo-scandal-shouldnt-shock-anyone-modern-slavery-is-a-pandemic/ (accessed 9 August 2020).

[72] See Chon, supra n. 65, p. 82; Andrew Griffiths, “Brands, ‘Weightless’ Firms and Global Value Chains: The Organisational Impact of Trademark Law” (2019) 39 Legal Studies 284–301.

[73] Bodó, supra n. 63, p. 18. See also Alan McQuinn and Daniel Castro, “A Policymaker’s Guide to Blockchain”, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (April 30, 2019), available at https://itif.org/publications/2019/04/30/policymakers-guide-blockchain (accessed 28 September 2021).

[74] See Pérez et al, supra n. 47.

[75] See Baker, supra n. 70.

[76] See Sara Saberi et al., “Blockchain Technology and its Relationships to Sustainable Supply Chain Management” (2019) 57/7 International Journal of Production Research 2117–2135, p. 2020.

[77] Niezen, supra n. 7, p. 202.

[78] Karen Yeung, “Regulation by Blockchain: The Emerging Battle for Supremacy between the Code of Law and Code as Law” (2019) 82 Modern Law Review 207–239, p. 235. Cf. Primavera De Filippi and Aaron Wright, Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code (Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2018), p. 210.

[79] Interview with US blockchain expert, Project No: BL CHEAN 23711 (RMIT), Project title: “The impact of blockchain in the supply chain: towards improved traceability and authentication”.

[80] Christine Parker and Fiona Haines, “An Ecological Approach to Regulatory Studies?” (2018) 45 Journal of Law and Society 136-155, p. 146. See also Primavera De Filippi and Félix Tréguer, “Wireless Community Networks: Towards a Public Policy for the Network Commons?”, in Luca Belli and Primavera De Filippi (eds.), Net Neutrality Compendium: Human Rights, Free Competition and the Future of the Internet (Cham: Springer, 2016), ch. 10, p. 269.

[81] Cf Nicolas Suzor, Tess Van Geelen, Sarah Myers West, “Evaluating the Legitimacy of Platform Governance: A Review of Research and a Shared Research Agenda” (2018) 80 International Communication Gazette 385-400. For well-known legal formulations of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, including “freedom to … seek, receive and impart information and ideas”, see, for instance, Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948, Art. 19; European Convention on Human Rights 1950, Art. 10; UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, Art. 19. See also UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Freedom of Information: The Right to Know (2011), available at https://uncaccoalition.org/resources/access-to-info/freedom-of-information-the-right-to-know-unesco.pdf (accessed 8 February 2022), p. 16.

[82] Centre for Social Justice and Justice & Care, “It Still Happens Here: Fighting UK Slavery in the 2020s” (July 2020), available at https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/core/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/It-Still-Happens-Here.pdf (accessed 24 August 2020), p. 71.

[83] Baym, Swartz, and Alarcon, supra n. 12, p. 403.

[84] Iansiti and Lakhani, supra n. 49, p. 127.