1. Introduction

The InVisible Difference Project is a three-year Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project, which examines the intersection between disability, dance and law. It asks questions surrounding authorship and ownership in dance made and performed by disabled artists, why disabled dance is almost entirely absent from our cultural heritage and how can audiences better view and review disabled dance.[1] On 26 November 2014, InVisible Difference hosted its second annual collaborative event, the “Disability and the Dancing Body Symposium”.[2] This event, which was open to the public and held at the Siobhan Davies Studios in London, was designed to steer the remainder of our research into areas identified as important by stakeholders in dance.

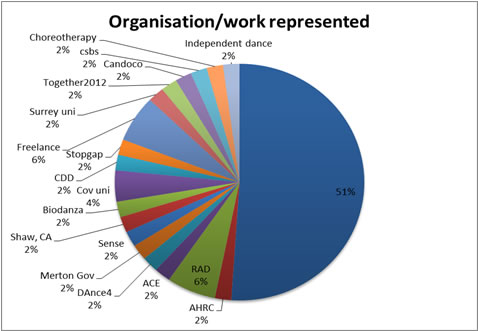

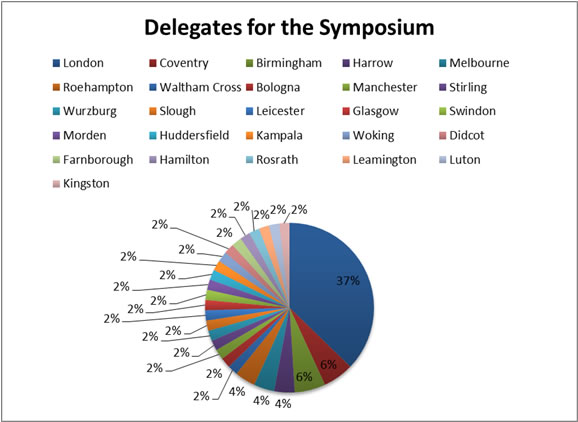

All tickets to the symposium were taken up in advance and seventy-two participants attended on the day. The event reached 691 people through our social media outlets. The professions and organisations represented at the symposium are shown in Figure 1.[3] The geographical dispersion of participants is shown in Figure 2. Both figures demonstrate the demographical diversity of the participants. The symposium proceeded by way of a keynote address from Australia via Skype, two panel presentations followed by discussion, three live dance performances after the lunch break and a final panel and discussion followed by general plenary discussion. The following reports on the symposium itself and analyses the new data it generated.

2. The Keynote Address

The keynote address was given by Caroline Bowditch, a dancer, choreographer and activist of international repute. Bowditch spoke about the opportunities available to her as an artist living in Scotland. In adopting the social model of disability, she contended that she might not be able to claim to be a ‘disabled artist’, as her opportunities in Scotland are wider than in many places, arguably approaching level.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Using Thurley’s “heritage cycle”[4], Bowditch explained that people begin to value something as “cultural heritage” when they understand it.[5] By valuing the material, people wish to care for it, and by caring for it, there is a desire to enjoy it, and by enjoying it, people seek to understand it. Where disability dance is concerned, this virtuous cycle is broken at two places: understanding the material and valuing the material. However, Bowditch argued that there is a growing desire within publics to understand the work being viewed. She pointed to a growing engagement with disabled dance as evidenced by the sold-out performances at the Unlimited Festival and her experience with touring “Falling in Love with Frida”.[6] This growing interest is closely linked, she contended, with increased funding support,that can lead to higher quality work.

Bowditch then posited a question: if our cultural heritage is made up of things that society appreciates, and is therefore proud of, is society proud of disabled dance? This begged questions about the general absence of disabled dance in our cultural heritage memory institutions, about perceptions of quality of work being produced and about how we determine exactly when something is deemed “valuable” (i.e. is it when it becomes a commodity?). Bowditch concluded by noting the commercial value of indigenous art to the Australian economy, which might serve as evidence that cultural heritage is indeed defined by its value as a commodity.

3. The Symposium Panels

The keynote address was followed by three multi-disciplinary discussion panels focussing on key themes within InVisible Difference.

Panel one: The first panel, “Disability Dance and Cultural Heritage: Why is Disabled Dance Almost Entirely Absent from our Cultural Heritage?”[7] chaired by Charlotte Waelde, Co-Investigator on InVisible Difference and Professor of Intellectual Property Law at the University of Exeter, was aimed primarily at the issue of presence and preservation of disabled dance within our memory institutions.

The first presentation was by Stine Nilsen, Artistic Co-Director of Candoco Dance Company, who discussed the foundation of Candoco and initial reactions to its programme. She reported that the arts councils quickly funded dance created and performed by disabled dancers, which suggests that value has been assigned to this art form. Over time, Candoco’s impact increased; their films were shown around the world, they were asked to travel to promote them and the British Council supported that travel financially. Candoco’s work was new and groundbreaking, eliciting polarised responses from society, some of them “proud” and others “not so proud” that disabled artists were more visible in the contemporary dance scene. This offered some insight into how society values dance performed by disabled artists and the necessity for a critical mass of disabled performers to create quality work. Nilsen closed by suggesting that the pride that is often associated with Candoco’s work over the last two decades should be translated into momentum for inclusion in our cultural heritage.

Fiona MacMillan, Professor of Law at Birkbeck, University of London, discussed intangible cultural heritage, continuing the consideration of whether something becomes cultural heritage when it becomes valuable as a commodity within society. MacMillan discussed the Wikipedia definition of cultural heritage[8] and suggested that who decides what constitutes cultural heritage, and what criteria are used to decide this, remain opaque. Deciding what is valuable and worth preserving for future generations is limited by the politics of the present and such decisions are linked to concepts of identity and community, which themselves are multi-faceted ideas. Yet, it is the community that decides what should be preserved as cultural heritage. She suggested that while those in disabled dance may be a community in itself, it is also part of the wider community of dance. How it locates itself in relation to that wider community will influence how it might build value for its own community and so a place in our cultural heritage.

Ruth Gould, Artistic Director of DaDaFest, discussed the presence of disabled artists in dance, suggesting that there is an artistic imbalance in dance performance. Despite some DaDaFest post-performance discussions, claiming true equality between disabled and non-disabled dancers, Gould argued that inequality persists because the trained dancer and their “ballet bodies” continue to dictate what dance is. In short, the presence of the disabled dancer is affected by the perception of what constitutes “real” dance. When she started dance at the “relatively old age of 23”, Gould reported, she was able to use her body in ways that were different because she was not a traditionally trained dancer. However, in order to progress in dance, she was expected to perform a series of tests that were designed to ensure a physical conformity to the “typical” dancer’s body. It did not matter how good your performance was so long as your body could do these “fundamental” things. Gould argued that a divide still exists between the two communities and that this, and the practices that it permits, will ensure that the non-disabled dancer will always look more refined, and so her work will be more valued and seen as worth preserving as our cultural heritage.

Jane Pritchard, Curator of Dance at the Victoria and Albert Museum London, discussed the documentation of intangible heritage, indicating that there are numerous sections of society that need preservation; a fact that generates competition and the necessity for preferencing. There is a lot of material that is invisible because they come from groups of which society is not particularly aware. She noted that dancers with one leg were considered fashionable in the 19th century, but this is an isolated example. Latterly, a group of Spanish dancers, including one dancing on his stumps, performed in London and the Spanish ambassador asked that the group be banned from performing, as the disabled dancer was “disrespectful to Spain”. Despite the production being hugely successful in Paris, it was less so in London; the disabled dancer was removed from the production. Pritchard also gave examples of written records of disabled dance, few of which were written from “an intelligent perspective”; many were dismissive of disabled artists who are rarely named and on occasion referred to only by their disability (e.g. “the dancer with one hand”).

Key themes from this panel included a general sense that great strides have recently been made in the recognition of disabled dance within society, but that we are still some distance from disabled dance being considered a part of our cultural heritage. There are isolated examples of disabled dance within our memory institutions, but they are few and the surrounding narrative tends to focus on the disability rather than the dance. Challenges remain around notions of identity, community and commodification, and what these concepts mean for the preservation of disabled dance and their importance in providing pathways to our cultural heritage. In relation to the valuing of disabled dance, challenges remain with audience literacy, which tends to be polarised and with social (dance community and audience) perceptions of the “acceptable” dancing body that is invariably rooted in the ballet body.

Panel two: The second panel, entitled “Disability, Dance and the (Legal) Rights Frameworks – ‘Support Structures’ for the Disabled Dancer”,[9] was chaired by Dr Abbe Brown, Co-Investigator on Invisible Difference and Senior Lecturer at University of Aberdeen. It brought together legal academics and a practitioner to explore the idea of “support” within the disabled dance community.

The first speaker was David McArdle, Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Stirling, who discussed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the European Convention on Human Rights and the UK Equality Act 2010. McArdle stated that the UN Disability Convention addresses two things: participation and access. After identifying the provision that covers dance and sport, he explained that judgments interpreting the Convention stipulate that you must treat the individual as an individual and not as a class of disability. The UK’s domestic equality legislation must be interpreted in parallel with this international law, which means that legislators and judges must think flexibly about how to interpret the law. Unfortunately, UK law is not in keeping with international law insofar as it does indeed categorise individuals based around their disability. It also, however, acknowledges that disability is an evolving concept, and this should be borne in mind when considering how the law might support the disabled dancer.

Luke Pell, performance maker, discussed what dance means to him, and called for support networks to consider the uniqueness of the dancer. Pell probed questions around whose voice is privileged in records of cultural heritage and challenged the colonising effect that support for disabled dancers can have (i.e. articulating the idea of “colonised bodies”).[10] He argued that the privileged voices tell others what they should prefer, and indeed what they should look like, and, as a result, they shape support networks. However, support from the perspective of the supporter is not necessarily support from the perspective of the supported; particularly if that support, designed from the privileged actor’s position, does not take into account the supported community’s situation or desires.[11] Referring to his own experience, Pell noted that institutional requirements could also limit the nature and utility of the support that dancers can receive. He concluded that the voices which dictate the colonisation of the body do not take into account the uniqueness of the bodies that exist in dance and he noted with satisfaction, programmes at Coventry University that are designed to support the individual needs of dancers, bearing in mind the uniqueness of their bodies.

Shawn Harmon, Lecturer in Law at the University of Edinburgh, discussed legal frameworks for medical and disability support and how “support” for patients (which includes disabled dancers) is construed under that paradigm. Echoing McArdle, he identified how the models of disability utilised in domestic legislation are contradictory to that within the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, with the latter using the social model and the former being grounded firmly in the medical model. Medical law is very conscious of disability, but Harmon emphasised that its reliance on the medical model tends to signal a defect in the patient (or individual) accompanied with a (virtuous) drive to fix what is “wrong” with the individual, to “normalise” them. Through this marginalisation of individuals, medical law makes them invisible; and through seeking to normalise individuals, it devalues them. Harmon felt that more needs to be done to connect the medical and disability communities, with particular focus on training within the medical community and the need to get future healthcare workers to better understand disabled individuals – by experiencing them in non-medical contexts, such as the dance studio and performance stage. This, in turn, will allow them to offer more effective support to disabled dancers.

Colette Conroy, Senior Lecturer in Drama at the University of Hull, discussed audience responses, recognition and misrecognition in dance, and how this supports dancers. First, she explained that recognition is a three-part theme of love, esteem and respect, and that structures designed to remove exclusion still exclude, insofar as models of inclusion require excluded groups to adopt characteristics of the exclusive (included) culture. Conroy argued that we should maintain the freedom to say in a neutral way whether work is good or bad. Disabled dancers do not wish to be viewed as “good, for an amateur performance”. Decades ago, they were anxious to be viewed as community dance performers and their art-as a form of therapy. But now they wish to be viewed through the same framework of excellence as is applied to non-disabled dance and they are ready for harsh criticisms. Importantly, the evolution of disability performance has created a new culture of recognition, but there needs to be more ambition for the audiences to engage with the work, not just the artists.

Mathilde Pavis, InVisible Difference PhD Candidate in Law at the University of Exeter, closed the support panel by discussing the benefits of copyright protection for dance artists. Pavis discussed her experiences in asking artists what they would like the law to do. Her research suggests that artists do not often engage with the copyright law and feel happy to continue to operate as they had always done. She countered this disinterest in the law by highlighting that copyright can be a way of securing income from the work which could help negate the effect of budget cuts to artists’ funding. Pavis also stated that while artists may not be engaging with copyright law, producers are engaging with it. In discussing copyright more explicitly, Pavis noted that copyright does not have regard to disability; it examines the finished product and not the characteristics of the creator. It does not offer better or different protection simply because the artist has a disability.

Key themes from this panel revolved around the limits of law; law’s focus on particular issues are informed by particular perspectives and prejudices, and do not focus on the issues those involved in disabled dance might see as being of central concern. Copyright and disability law exist and seek to facilitate opportunities within which to work and to offer support mechanisms, but they could be much better suited to the needs and aspirations of disabled dancers. Importantly, the law is not static. If scholars, lawyers, creators and dancers consider legal provisions to be inadequate, they must be activist and engage with policymakers more consistently. This, together with improved education for dancers, the medical professions and audiences can lead to more effective and iterative support for individuals.

Panel 3: The final panel, entitled “Disability Dance and Audience Engagement”,[12] was chaired by Dr Karen Wood, Wolverhampton University and InVisible Difference Research Assistant at Coventry University. This panel debated how audiences engage with performances by disabled artists with a view to improving comprehension of the language used by audiences and their interactions with the work.

Catherine Long, contemporary performance artist and dancer, highlighted the exclusivity of dance by discussing how she became a dance artist. Long never intended to become a dancer, which she viewed as an exclusive field. She echoed Gould’s observations about how disabled bodies do not often fit the dancer ideal. Long then discussed what is meant by “critical discourse”, questioning the assumption of a perceived lack of critical language. She asked whether a different language is needed to describe disabled dance and whether having a different language would de-value disabled dance. Long conceded that it might, alternatively, have the effect of acknowledging the particularity of disabled dance; having a similar language may be akin to attempting to erase the disability, which may constitute a failure to acknowledge the dancer’s identity.

Sophie Partridge, disabled actor, writer and artist, discussed audience engagement in theatres. She further problematized the lack of audience literacy and questioned whether a different discourse was required. She also questioned whether reviews were important to artists. The general consensus was that they were an important aspect of making work and getting it viewed by audiences.

Donald Hutera, dance, theatre and performance journalist with The Times, discussed audiences from the perspective of a reviewer. He reported that he tried to be very careful in his use of language when describing dancers and recalled a review he had written for Candoco, after which he was questioned by the company about how he had described a dancer.

Kate Marsh, InVisible Difference PhD Candidate at Coventry University, discussed performance as a disabled artist. She stated that when we enter into the viewer/performer relationship, our socially and culturally constructed/informed ideas of disability and impaired bodies are integral to our interpretation of what we see and how we experience the encounter. The person that is the dancer often recedes with the consequence that the language we use to critique and discuss dance, made by impaired dancers, relies heavily on the medical model hindering the development of thinking in this sector. In response to Hutera’s observation, that he sees a dancer with one leg and wonders what it would be/feel like to have one leg, Marsh noted the colonial fascination (i.e. the experience of impairment as curious and “other”). She wondered whether the critic would wonder the same about a “normal” physicality? Marsh concluded by emphasising that we need not ignore the specifics of a dancer’s body or disability. We must do more to find a language that can explore that body in performance without an implied narrative of trauma or overcoming, so that we can arrive at the point of the performance.

Matthew Reason, Professor of Theatre and Performance at York St John University, considered the freedom of audiences to be “educated” in what they are viewing. Audiences generally like to talk about performances with their friends or family and these discussions etch on their memory details about the experience. Some audience members are not interested in participating in questionnaires or post-show discussions, which can limit our ability, as academics, from influencing their perceptions or language. Reason advocated an acknowledgement that audiences’ freedom to be educated (or not) must be considered.

The key elements of this panel’s more open and organic discussion related to how we use language to describe what we have seen, the importance of having a reviewer write about your work (in appropriate terms) and how audience education needs to be carefully considered.

4. Participant Data

In addition to reporting on the project, and further exploring in a discursive manner some of the central questions we have posed to date, the symposium served as a means of gathering further data on questions of interest, from this large and diverse sample. However, settling on the best method proved challenging. We considered a variety of methods for collecting data from the participants (e.g. entry and exit surveys, sticker charts on substantive issues, questionnaires) and rejected many of them. For example, surveys and more detailed questionnaires were seen as both too restrictive in the answers they might elicit and too burdensome for participants after a long day of engagement. Ultimately, the most sound and potentially successful method for securing the richest information was to utilise 200 postcards on which participants could leave comments. The postcards were distributed around the symposium space and 150 of them asked the participants to complete two incomplete sentences already supplied. These leading questions elicited data as follows:

- “This made me feel…”: Responses to this question, in the aggregate, indicated that participants welcomed the opportunity to engage with the issues that were the focus of the panels, some of which they were familiar with. However, they were also interested in learning more about the wider issues such as law and its role in dance and how performance work can be preserved. Participants highlighted companies that were doing work in the areas of disabled dance including Stopgap Dance Company. They also reported being pleased with the breadth of the disciplines represented at the Symposium.

- “The day made me feel differently about…”: Broadly, the greatest number of participants reported that the symposium made them feel differently about the support that is currently in place and how they can utilise the range of support networks that exist. They also reported that change in support is still needed and some reported feeling motivated by the issues discussed to take action. Some simply wanted to know more. Overall, the value of interdisciplinary approaches to research was confirmed.

- “I think you need to examine…”: Some of the responses suggested that InVisible Difference should also look at cognitive disabilities and therapeutic dance, although no indication was given as to what elements were most deserving of investigation. Some reported that the symposium made them think about, or reconsider, their own personal reactions to questions of heritage, support and audiences.

- “The words I’d use to describe the performance are…”:[13] While including a live performance in an academic event will be an alien concept to most lawyers, it assisted our audience in stimulating thinking around the research questions. With regard to the performances themselves, they were viewed as a welcome break from the intensity of the discussions. Moreover, the participants were extremely positive about them, using words like “rare”, “humorous”, “mesmerising”, “thought provoking” and “passionate”, to describe the pieces.

- “I would like to find out more about…”: This question resulted in a large variety of responses ranging from inquiries about involvement in the project, finding out more about copyright and law, what documentation is coming out of the project,[14] how the discussions are being continued in higher education and paid opportunities for disabled artists.

We also provided fifty blank postcards so that more general or unprompted comments could be obtained. They allowed participants to express opinions on matters that did not fit into our more leading sentences. These unsolicited responses indicated that:

- language can be very important and empowering/marginalising and the use of language throughout the day was good (e.g. that “artist” and “dancer” were used);

- participants welcomed the opportunity to engage in the issues surrounding dance, disability and performance without the necessity of appearing overly politically correct, which was a rare opportunity;[15]

- dance made and performance by disabled artists is not, and should not be viewed as, simply a niche market of the modern era; it has history and cuts across all forms of dance, so the drive to raise its profile is both legitimate and important and will inevitably raise passions; and

- there is an interest in the issue of cultural heritage and what it might mean for practice and for individuals.

Some responses also identified issues that had not been raised in the research, but that were felt to be important (e.g. the position of learning disabled dancers).[16] Also, some queried who from the relevant communities (dance in particular) were absent but should have attended, so that outreach could be undertaken and new dialogues opened up.

5. Conclusions

It was apparent that while the law has its limitations in facilitating this field, it does have a role. It is important that there be interaction with legal frameworks in order to identify where support works and where it is lacking. Several symposium participants suggested that we are now at a “tipping point” and that this might be a critical time. Others expressed frustration that some of the same discussions have been ongoing for years, including the idea that we are at a “tipping point”. They suggested that much more is needed to move dance made and performed by disabled artists out of the periphery and into the mainstream. To do this, a range of communities must to come together to effect change. This connected to the discussions surrounding cultural heritage. The community of disabled dance must more overtly celebrate its identity, but also celebrate its rising position within the wider dance community. To finally claim its place in the cultural heritage of our society, it must additionally create more opportunities for disabled and non-disabled people to discuss disabled dance and stoke the interest that is beginning to be expressed. Better informed audiences, better equipped to know what to expect and to look for in disabled dance, are critical, and they will have knock-on effects for audience attendance and new avenues for engagement.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Siobhan Davies Studios, which was aptly described by one of our participants as “a Cathedral for contemporary dance”, for hosting the symposium and assisting us on the day. We would also like to thank the staff at the Centre for Dance Research (C-Dare) at Coventry University for their support during the day. We would also, of course, like to thank the AHRC for its kind support of InVis.

* Lecturer in Regulation and Risk, University of Edinburgh School of Law.

* Associate Research Fellow, University of Exeter.

* Senior Lecturer, University of Aberdeen, School of Law.

* PhD Candidate in Performing Arts, Coventry University.

* PhD Candidate in Law, University of Exeter.

* Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Exeter Law School.

* Professor of Dance, Coventry University.

* Lecturer in Dance, University of Wolverhampton and Research Assistant, InVisible Difference project, Coventry University.

[1] “InVisible Difference” available at http://www.invisibledifference.org.uk/ (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[2] The first event held in 2013, was a by-invitation workshop and forum called “Intersections”, which opened up dialogue between dance artists, lawyers and disabled people. The third and final major event, scheduled for the fall of 2015, will be an interdisciplinary conference open to the public featuring a live performance.

[3] The 51% represents attendees who provided no information on their background.

[4] Culture in Development, “What is Cultural Heritage” available at http://www.cultureindevelopment.nl/Cultural_Heritage/What_is_Cultural_Heritage (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[5] Bowditch’s keynote address can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cRMvs91kRU.

[6] See: “Falling in love with Frida promo Caroline Bowditch” (2014) available at http://vimeo.com/102615217 (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[7] Panel one can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cRMvs91kRU (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[8] Cultural heritage is described as “…the legacy of physical artifacts and intangible attributes of a group or society that are inherited from past generations, maintained in the present and bestowed for the benefit of future generations.” Wikipedia, “Cultural Heritage” available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_heritage (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[9] Panel two can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CNMTs9V4bQ and here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VgZreOGffs (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[10] This is a theme that was also picked up by Harmon in his talk about how the medical law framework supports disabled dancers.

[11] In this regard, Pell made reference to a man on his train into the symposium. The man was walking extremely slowly to his seat, though he was not causing any obstruction to anyone looking to pass him. Nonetheless, a woman from the other end of the carriage took him by the shoulder and hurried him to his seat. This may be seen as supportive from the woman’s perspective, but it may also be seen as intrusive, and it certainly did not take into account the unique requirements of the man’s body.

[12] Panel three can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8deW2-9hF1E (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[13] The performances were of work in progress. Dan Daw performed Beast, Welly O’Brien and Kate Marsh performed Famuli, and Kimberley Harvey, Robert Hesp, and Kitty Fedorec performed Moments Revisited.

[14] We have a comprehensive list of publications and outputs to date available on our website at: “InVisible Difference: Publications” available at http://www.invisibledifference.org.uk/research/publications/ (accessed 23 Apr 15).

[15] Observations on this point reflects earlier findings in InVisible Difference that the reluctance to discuss controversial issues around disability and dance stems in part from a fear of offending others. The symposium data demonstrate that until these discussions take place, problems remain hidden or ignored.

[16] On this point, some expressed disappointment that cognitive disability did not feature in any meaningful way. To provide us with a workable focus, however, our attention has been on the professional artist and not participatory or community dance. The professional artists we have been working with have been almost entirely physically disabled. We do recognise that the fields of professional, contemporary dance, therapeutic dance and participatory dance do overlap, and this is something we aim to address in our final year or beyond our current project.

Firstly i think it is outstanding that this subject has finally been given some consideration and acknowledgement and is finally being bought to the forfront.

I have fibromialgia and E.d.s. ive always loved dancing although ive never taken classes, however i am aware when im dancing my pain can varie and in turn my performance will differ accordingly. Some times dance can be very painful yet another time dance can reduce my pain levels. Im also aware that after a dance i can not determine if i will suffer excrutiating pain and exhaustion or feel totally relaxed.

After speaking to some of my friends in the fibro group who were in reciept of benifit support, we were all in agreement that there was an overall fear of exposing there abilities and pleasure to dance, due to the fact they may not be able to move let alone dance after an initial dance and this would be one of the reasons that would hold them back from the challenges that lay ahead if they were to join a class, they also feared accusations of benifit fraud. For a person with fluctuating conditions, fear of these judgements and loss of income can and does imprison ones love for dance. We would like to add we might dance for a limited time and it feels exhausting yet exhillerating, and we would happily do this knowing we will pay for it in pain for maybe several days, unknowing if we can sum up the ability to get a meal after, due to muscle spazms and chronic fatigue, along with all the other stuff, however we could not afford to lose the financial support we already have had to fight so hard for. We have invisable fluctuating conditions, so we feel restricted to dance in issolation. I am so greatful that you are looking at addressing finances and pay, or not, regarding dance and within this i urge you to consider raising these fears and restrictions with the appropriate authorities in hope that it will stop the judgements and ignorance that stops so many disabled from coming forward in fear of losing the money they so depend on for there after care, also restricting people from ever daring to try and reach there ever fluctuating full potential thus restricting those of us affected from enjoying our life to the fullest.